There’s an interesting read in this month’s Harvard Business Review (HBR): The Hidden Cost of Inconsistent Decision Making. The article explores the implications of variation in employee judgment and specifically, how to solve for that variation. In essence, the article was about Mura – the Japanese term meaning waste of unevenness / variation.

Like many of my clients, the organization featured in the article hadn’t previously considered the impact inconsistency had on cost. For the company in question, it turned out to be in the billions.

Causes of Internal Bleeding

How does that much hemorrhaging go unnoticed? Because the pain of inconsistency isn’t obvious, particularly in office settings where there are fewer physical indications of flaws in the system. Also because the process is thought to otherwise be stable. Thirdly, as was mentioned in the article – and is true in many organizations – the occurrence of variability was expected and accepted as part of the cost of doing business.

Interestingly, the impact of variation on performance does not go unnoticed in Lean methodology. In fact, Mura (unevenness / variation) is considered to be responsible for creating Muri (overburden on employees / processes) and Muda (waste resulting from any activity or process that does not add value).

Beyond Eliminating Waste

Muda is undoubtedly the most well-known, most often and most easily addressed category of waste. In my view this is because the eight wastes classified as muda are easily seen and understood:

- Transport – Moving people, products and information

- Inventory – Storing parts, pieces, documentation ahead of requirements

- Motion – Bending, turning, reaching, lifting

- Overproduction – Making more than is immediately required

- Over processing – Tighter tolerances or higher grade materials than are necessary

- Defects – Rework, scrap, incorrect documentation

- Skills – Under utilizing capabilities, delegating tasks with inadequate training

- Waiting – Idle time created or wasted when material, information, people and equipment are not ready

Unfortunately, many Continuous Improvement journeys begin and end here. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, many companies only realize the short-term success that results from addressing Muda because they pursue Lean for the wrong reasons.

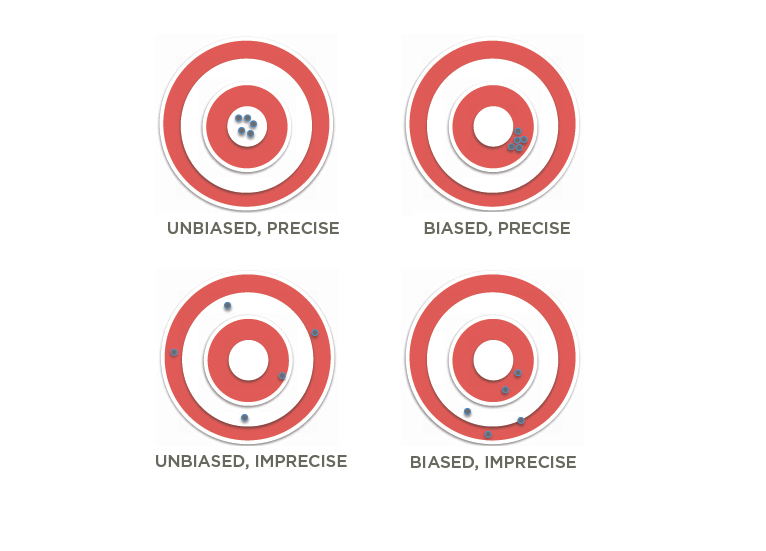

They want to use Lean tools without adopting Lean thinking. These organizations are after the business outcome of cost cutting and so they work to address the “low hanging fruit”, the “quick win” of addressing Muda and call it a day. In addition to sustainability issues, the glaring problem with only focusing on Muda is that it doesn’t remedy instability in the process and as Deming reminds us, “Uncontrolled variation is the enemy of quality.”

Challenges to Exploring Variation

Even those who believe in the larger impact Continuous Improvement should have on culture and governance still shy away from addressing variability. I believe this hesitation has to do with the fact that exploring Mura requires more time and more expertise than addressing Muda.

This is where Six Sigma comes into play, when things get granular – and slow and granular isn’t as sexy as obvious and fast. Solving for variation is to purposely sweat the details and involves a lot of data collection, organization and statistical analysis – not as many people can or want to get involved in parsing through data sets.

In addition to giving management agita, the front lines also sometimes hesitate to tackle consistency. “We’re not robots,” is a common refrain. There is fear in that statement. Fear that they don’t matter, that their value (skill / experience/ contribution) is taken for granted and holding on to the status quo is the only guarantee – in their view – that they are seen. This sensitivity to change is why how Lean is implemented matters so much.

Solving for Variation is only Win Win

Nonetheless, before the post Muda honeymoon ends, operations leaders should absolutely turn their attention to inconsistencies in the process. As the article shows, the upside is huge. Not sometimes huge – almost always huge.

Given the reality that most Lean attempts are – at least initially – financially motivated, confronting variability ensures that your efforts to adopt Lean will continue to yield impressive cost cutting results. But better than that, it makes sustainability more likely – i.e. future benefits.

Moreover, the process of understanding inconsistency leads to alleviating the burden of unpredictability on employees up and down the food chain. This means less stress all around resulting in happier employees with the time and space to think about how to create value. And that is when things start to get interesting.